2.1 Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA)

EIA is a process to identify and consolidate information about the environmental effects of certain proposed projects, enabling informed decision-making and public participation. This process does not dictate final decisions but should encourage integration of environmental matters into the early planning, design and approval of projects. EIA first entered English law through the Town and Country Planning (Assessment of Environmental Effects) Regulations 1988 (implementing the first EU EIA Directive22), having emerged as a concept in the USA in the late 1960s.23

In England, EIA has since developed through a range of legislation covering different types of projects. For most people, the most familiar of these will be the Town and Country Planning (Environmental Impact Assessment) Regulations 2017 (referred to subsequently as the ‘EIA Regulations’). Other EIA legislation applies to, for example, Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs), drainage improvement works and certain agricultural and forestry activities. There is, however, much similarity between the different EIA regimes, all of which were intended to transpose the EIA Directive or its predecessors.24 Many of the issues associated with the implementation of the EIA Regulations may also be present in relation to the other EIA legislation.25 Hence, whilst we generally refer to the EIA Regulations and therefore to EIA in the context of town and country planning, we also refer to other regimes, for example for NSIPs, where relevant to do so.

EIA has two optional preliminary stages whereby proponents can require the decision-maker (local planning authority or Secretary of State) to give an opinion on screening and/or scoping. Screening is to determine whether a project is of a type which requires EIA. Scoping is to determine whether a full assessment is required and, if so, what it should cover. Thereafter EIA involves five main steps as follows:26

- the preparation of an environmental statement by or on behalf of a proponent

- public consultation

- consideration of relevant environmental information, including the environmental statement, by the consenting authority27

- the consenting authority arriving at a reasoned conclusion on the significant effects of the proposed development on the environment, and

- the consenting authority incorporating their reasoned conclusion into their decision whether and on what terms to grant consent for the development.

This process applies to categories of projects set out in the relevant legislation. For the EIA Regulations, those types of projects listed in Schedule 1 to the regulations are projects which will always require EIA. These include, for example, crude-oil refineries, nuclear power stations, motorways, and hazardous waste landfill. Those projects listed in Schedule 2 require EIA only when they are likely to have significant effects on the environment for reasons of the project’s nature, size or location.

The threshold to trigger EIA is high, resulting in only those projects most likely to be environmentally significant being subject to the process. In practice, EIA applies to very few projects relative to the number subject to development control overall. In the 12 months ending March 2023, LPAs in England received 395,624 planning applications, of which only 332 involved an environmental statement. This represents less than 0.1% of decided applications.28 The Government has identified between 10 and 20 NSIP EIAs per year.29

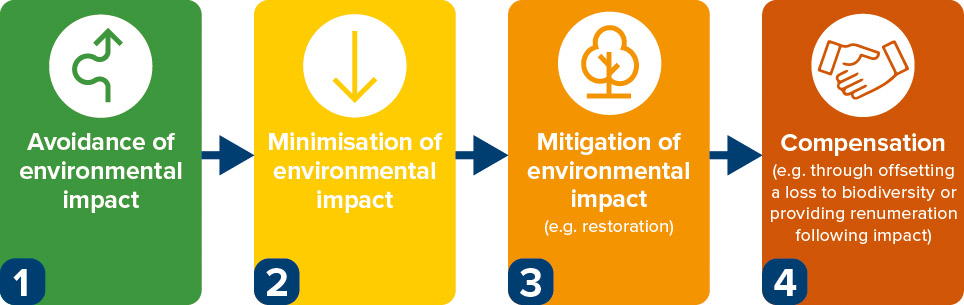

A mitigation hierarchy is an important aspect of environmental assessment, by which decision-making is encouraged to favour preventative measures such as avoiding and minimising environmental impact, and only adopt measures for mitigating and offsetting the likely significant impacts where prevention is not possible (see Figure 3). Through this mitigation hierarchy, EIA is used to identify measures to avoid, prevent or reduce and, if possible, offset likely significant adverse effects on the environment. 30 A project’s positive environmental effects must also be identified,31 and may be supported in decision-making.

Figure 3. The mitigation hierarchy

Flow chart shows step 1: Avoidance of environmental impact... Step 2: Minimisation of environmental impact... step 3: Mitigation of environmental impact (example restoration)... Step 4: Compensation (example through offsetting a loss to biodiversity or providing renumeration following impact)

In our view, EIA delivers its objectives by enhancing environmental awareness, compelling proponents and decision-makers to think through the environmental implications of proposed projects, and providing an opportunity for stakeholder consultation.

How far EIA leads to more environmentally beneficial outcomes is less clear. In a 2016 study only 13% of respondents felt EIA had led to extensive changes in project planning. Just over 4% suggested that EIA had led to the best environmental option being adopted. 42% of respondents thought EIA had mainly led to limited changes and only about 2% thought EIA had no effect on a project or on decision-making.32

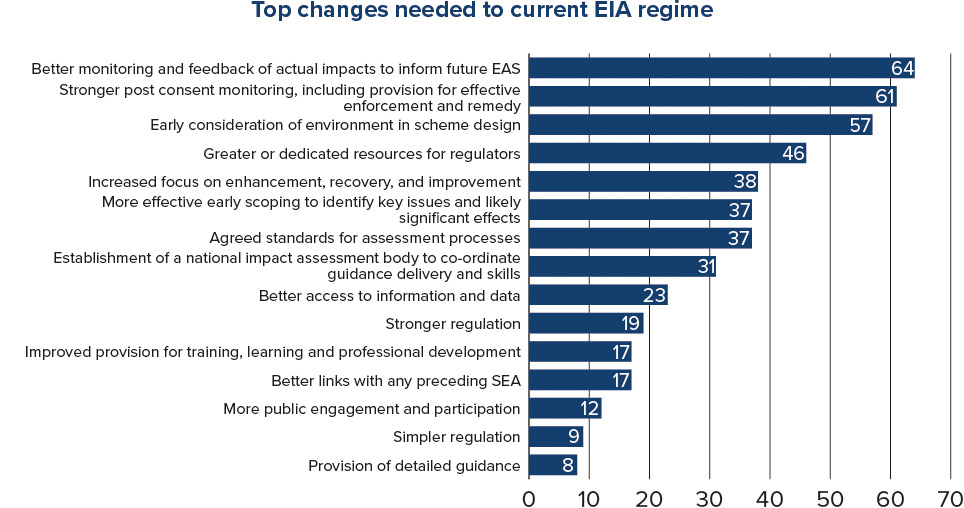

Government and others have criticised EIA for being time-consuming and bureaucratic, resulting in lengthy, inaccessible reports.33 The law could be clearer on the appropriate way to determine the indirect effects of projects34 and how to correctly determine the extent of a project35 – whether it forms a distinct ‘project’ which may have cumulative effects when considered alongside other projects, or would be more properly considered part of a bigger project. These judgments require skill and experience. For changes and improvements to the current EIA regime as identified by respondents to the practitioners survey, see Figure 4.

Figure 4. Identified improvements needed for the EIA regime by respondents to the practitioners survey

Figure 4 ... "Top changes needed to the current EIA regime". The graph is a vertical bar chart. Here are the proposed changes and their corresponding values from the practitioners' feedback: - "Better monitoring and feedback of actual impacts to inform future EAs": 64 responses. - "Stronger post consent monitoring, including provision for effective enforcement and remedy": 61 responses. - "Early consideration of environmental scheme design": 57 responses. - "Greater or dedicated resources for regulators": 46 responses. - "Increased focus on enhancement, recovery, and improvement": 38 responses. - "More effective early scoping to identify key issues and likely significant effects": 37 responses. - "Agreed standards for assessment processes": 37 responses. - "Establishment of a national impact assessment body to co-ordinate guidance delivery and skills": 31 responses. - "Better access to information and data": 23 responses. - "Stronger regulation": 19 responses. - "Improved provision for training, learning, and professional development": 17 responses. - "Better links with any preceding SEA": 17 responses. - "More public engagement and participation": 12 responses. - "Simpler regulation": 9 responses. - "Provision of detailed guidance": 8 responses. The bars provide a visual representation of the importance or priority of each proposed change as indicated by the number of responses from practitioners.

There are also criticisms about the practice of EIA, including poor resourcing of planning authorities, a lack of sharing of data and poor post-decision monitoring, evaluation and enforcement. We discuss these latter issues further in Chapters 3 to 5.

- Council Directive 85/337/EEC of 27 June 1985 on the assessment of the effects of certain public and private projects on the environment, [1985] OJ L 175/40.

- Scenic Hudson Preservation v Federal Power Commission 354 F2d 608 (2d Cir 1965); National Environmental Policy Act 1969 (USA).

- The first EU EIA Directive was amended four times, and those amendments have been codified into a single instrument, the EIA Directive. Domestic EIA legislation enacted before the passage of the EIA Directive (or before earlier amendments to the first EU EIA Directive) has been amended to give effect to changes made by the EU. More broadly, the EIA Directive is aligned with the Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context (“the Espoo Convention”).

- We refer to these regulations throughout this report as representative of EIA regulations in England generally. For comparisons of the different regimes, see Tromans and others (n 14) 54–58.

- EIA Regulations, reg 4.

- i.e. the relevant planning authority or the Secretary of State.

- DLUHC, ‘Historical Live Tables: January to March 2023 (Table P134)’ (2023) <www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/historical-and-discontinued-planning-live-tables> accessed 18 July 2023.

- Explanatory memorandum to the EIA Regulations, para 7.5.

- EIA Regulations, reg 18(3)(c).

- Ibid, sch 4 para 5.

- Urmila Jha-Thakur and Thomas B Fischer, ‘25 Years of the UK EIA System: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats’ (2016) 61 Environmental Impact Assessment Review 19, 31.

- For example, DLUHC, ‘Environmental Outcomes Report’ (n 11) s 3; MHCLG, ‘Planning for the Future’ (n 8) 57–58.

- R (on the application of Finch) v Surrey CC [2022] EWCA Civ 187.

- R (Wingfield) v Canterbury City Council[2020] EWCA Civ 1588